The metaphor behind the design of the new Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial is lost on no one in the remote and ordinary spots

where the civil rights movement unfolded.

“With this faith, we will be able to hew out of a mountain of despair a stone of hope,” King said in his 1963 “I Have a Dream”

speech.

Across the South, a half-century of difficult hewing has produced dozens of memorials at the still highly charged scenes of

murders, marches and triumphs. Among them, bus stops, lunch counters, a bridge and schools.

The first black president could shine a spotlight on this string of human rights pearls by securing U.N. World Heritage designation

for the civil rights movement.

When I moved to Alabama in 1999, most civil rights sites were unmarked, and many had been destroyed. Tourism offices and historical groups, out of racism and guilt, refused to embrace this great gift to the world. Rosa Parks, for example, had to share a

street sign with Hank Williams.

That has changed enormously. Now, in Montgomery, there are two Rosa Parks museums – one for children with a Disney-like “ride”

back to the 1950s – a city-sponsored civil rights trail, and new museums dedicated to Freedom Riders and the 1965 voting rights

march.

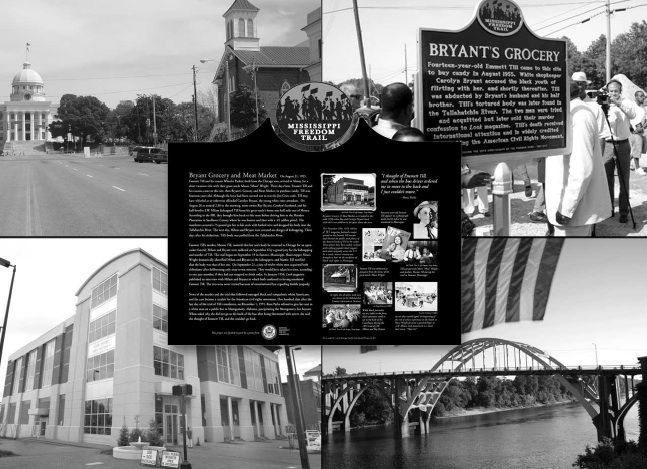

Clockwise from top left: The Alabama Capitol with Dexter Avenue Church at right; the Bryant's Grocery marker in Mississippi; the Edmund Pettus Bridge, site of the "Bloody Sunday" conflict on March 7, 1965; the Rosa Parks Museum; Inset: the back panel of the Bryant's Grocery marker.

In 2008, Dexter Avenue Church in Montgomery, where King used to preach, along with two African American churches in Birmingham (Bethel Baptist and 16th Street Baptist) were recognized by the Interior Department as worthy of world heritage status as sites key to the civil rights movement. They were put on a “tentative list” for eventual nomination as cultural icons that

“had a profound influence on human rights movements elsewhere in the world, particularly regarding nonviolent social change.”

But the National Park Service will need to add more movement sites to win UNESCO’s exacting approval, a process that would

take staff time and money, according to Stephen Morris, chief of international affairs at the National Park Service.

Chiseling new narratives into southern stone is a difficult task. The South is shadowed by the Civil War, arguments over who

owns history and cynicism at turning human rights tales into tourist trails. But such hewing has led to reconciliation, the

airing of centuries-old grievances and an integration of history that, until recently, was as “Jim Crowed” as water fountains

were in the 1960s.

Case in point: Money, Miss., a dried-up spot in the Delta between the old Yazoo & Mississippi Valley rail line and the turgid

Tallahatchie River, infamous for being the site of the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till on Aug. 21, 1955. I consider it the

most haunted of Mississippi civil rights sites, the crumbling bricks of Bryant’s Store a palpable reminder of the isolation

and fear that surrounded blacks.

On May 18, the state of Mississippi, with Gov. Haley Barbour’s support, erected in front of the store a historical marker

that describes Till’s death and significance. It includes a quote from Rosa Parks recalling her action four months after:

“I thought of Emmett Till, and when the bus driver ordered me to move to the back and I just couldn’t move.” When Till’s cousin

Wheeler Parker said to the dedication crowd, “This is the spot where we were when we came out of that store,” even tourism

officials felt a chill, recalled Ward Emling, Mississippi’s manager of film and cultural heritage, in an interview.

Few realized that as the ceremony took place, another small drama was playing out. The store is now owned by the grandchildren

of one of the jurors who acquitted Till’s murderers – men who later confessed in Look magazine. The juror and his all-white

companions are pictured on the marker. Yet his granddaughter cooperated in finding a spot for the marker, vetted its content

and advocated for it within her family, according to the marker’s designer, Allan Hammons. “For them to become advocates,

letting go and doing the right thing is a powerful statement,” he told me.

The Till marker was the first of 25 markers to be erected on a “Mississippi Freedom Trail” – this in a state notorious for

more lynchings (more than 500 between 1890 and 1950) and more civil rights murders (40 between 1954 and 1968) than any other

state Their sacrifice eventually led to the election of 800 black people to public office.

The trail was the third major civil rights initiative taken by the state in the past half-year. In December, Mississippi became

the first state in the nation to require a civil rights curriculum in kindergarten through 12th grade. In January, Barbour

pushed through the legislature $15 million as seed money for a Mississippi civil rights museum – a move widely linked to his

presidential aspirations but one that will lead to the first state-run, statewide civil rights museum in the United States.

Mississippi’s consequential efforts are precisely the kind of story deserving of world heritage designation.

This oped was published in the Washington Post Sunday Opinion page Aug. 28, 2011.